Since the end of World War II, trade liberalization and economic integration have been embraced by the more advanced economies as pillars of prosperity and global peace. During this period, global tariffs were gradually brought down and trade barriers were dismantled, facilitated by the rules and mechanisms of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), and later the World Trade Organization (WTO). Additional boosts to international trade were provided by the integration of former-communist economies into global markets, the proliferation of multilateral agreements, and the economic opening of China.

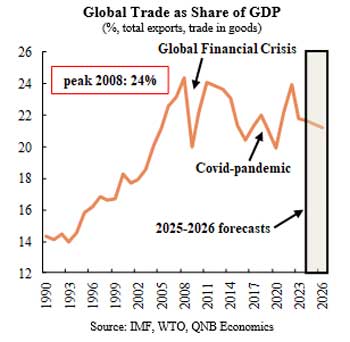

These developments helped push trade to record highs. In 2008, the sum of exports of all countries reached its peak of 24% of global GDP. But the rapid expansion of global trade flows then came to a sudden halt. The Global Financial Crisis (GFC) represented an abrupt interruption of the positive trend, as major economies entered recession and faced a financial crunch, causing consumer and business demand for goods to plummet. Growth in trade fluctuated sharply in the following years, amid increasing protectionism, geopolitical polarization, and the nationalist “America First” doctrine during the first Trump presidency.

In early April this year, on what has come to be known as “Liberation Day,” President Trump unveiled a sweeping package of tariffs that hit practically all countries. This unprecedented event placed the US at the epicentre of a major global trade shock, and marked the beginning of a period of high economic uncertainty. Countries rushed to put together comprehensive offer packages to soften the initially unyielding position of President Trump. The terms of bilateral negotiations extended beyond tariff levels, and included investment pledges destined to the North American economy, as well as the outright purchase of US goods, spanning from agricultural to energy products.

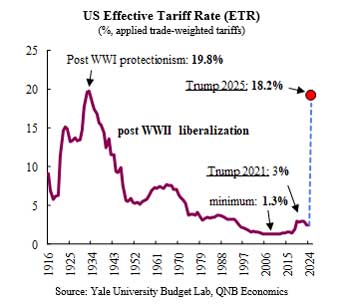

The conclusion of a first set of negotiations helped moderate uncertainty and discard the extreme case scenarios. Deals were reached with the UK, Japan, Indonesia, Vietnam, the Philippines, and the EU, narrowing the range of potential outcomes for the rest of the world, and slowly uncovering a new “high-tariff world.” The effective tariff rate (ETR) is a useful measure of the burden imposed on a country’s imports, measuring the average rate of tariffs weighted by the value of imported goods. The latest estimate points to an overall average effective rate of 18.2%, the highest level since the peak of 19.8% in 1933, a period of strongly protectionist policies.

this article, we discuss the key consequences of the new tariffs for the performance of the US economy.

Tariffs are set to have an impact on prices faced by US households and firms. Typically the “pass-through” effect of tariffs to final prices is not complete, since part of the increase in costs is absorbed via squeezed profit margins of US importers, as well as of foreign producers. Nevertheless, estimates of the final impact on prices are significant, in a range from 0.4 to 2 percentage points (p.p.) in headline inflation. Even in the more optimistic scenarios, the expected increment in final prices represents an important cost for households. As a result, higher tariffs are expected to curb household purchasing power, supressing overall consumption and economic growth.

On the production-side, higher tariffs raise input costs and disrupt supply chains, deteriorating competitiveness and lowering investments. Policy uncertainty and higher costs from tariffs reduce investment, particularly in manufacturing. As a result of higher tariffs, consensus growth expectations for this year have descended sharply, from 2.2% before Liberation Day, to 1.5%. This is a meaningful downgrade on the growth outlook for the US economy as a result of the new high-tariff reality.

Tariffs act as a tax on imports and are therefore a means to generate revenues for the federal government, contributing to reduce the fiscal deficit. According to the most optimistic estimates on the fiscal impact, the new tariffs to date could raise USD 2.3 trillion over the period 2026-35. Although, this is a substantial increase in resources for the government, the negative impact on the economy could diminish other sources of fiscal revenues. Furthermore, it is uncertain if current tariffs would be maintained beyond the end of President Trump’s terms.

All in all, higher tariffs create significant headwinds for the US economic growth outlook, as higher prices reduce household spending, and uncertainty and increased costs affect production and investment.